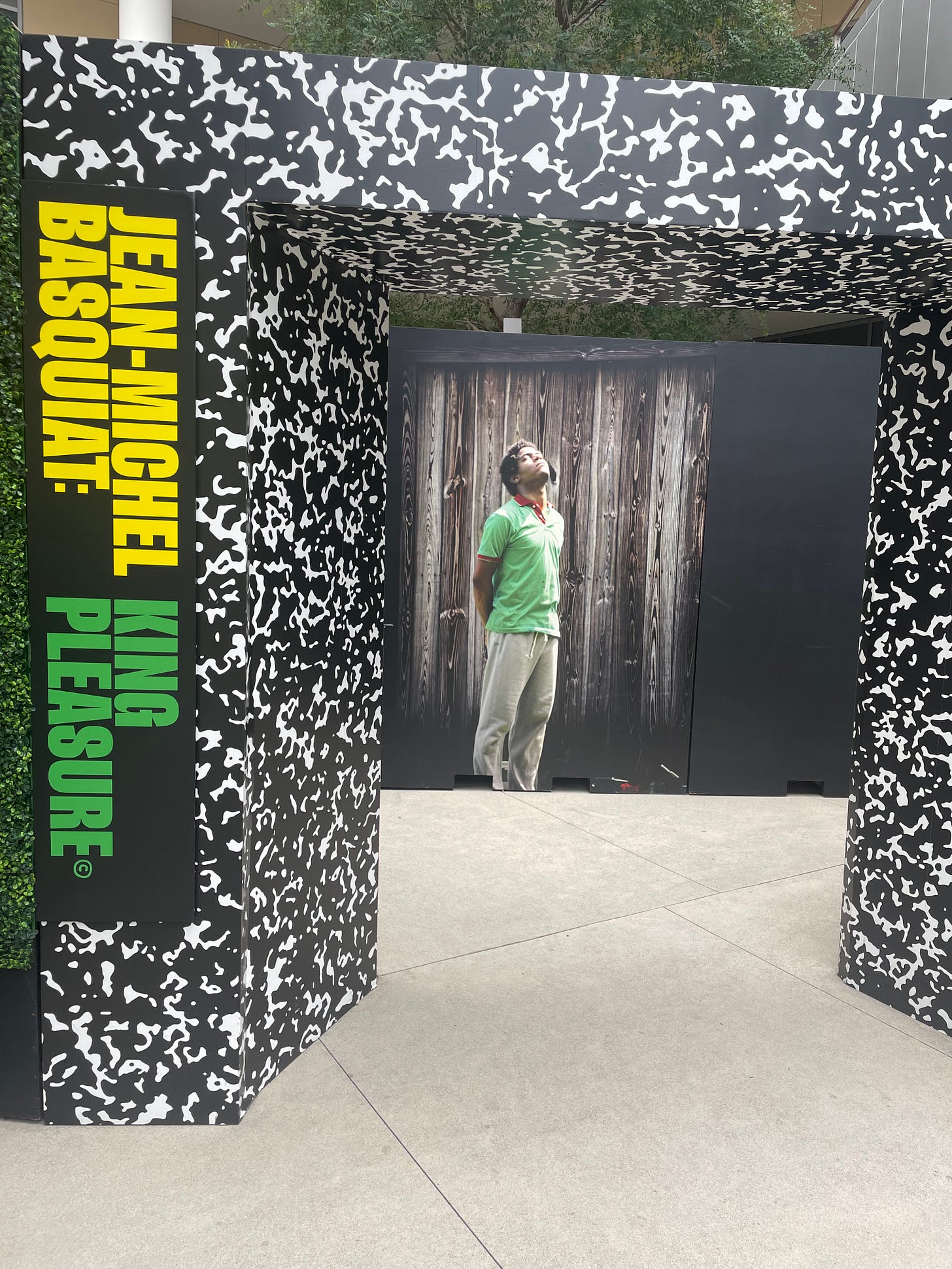

King Pleasure, on view in Los Angeles through the end of the year, offers a retrospective glance at the life and art of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Curated by his sisters and stepmother, the show illuminates over 200 artworks, with many showcased publicly for the first time. Replicas of Basquiat’s family brownstone in Brooklyn and his studio in NYC are prominently featured within the exhibition. While the exhibit could easily be perceived as just another addition to the capitalistic surge of the Basquiat brand, which now appears on everything from mugs to sweatshirts and Tiffany’s ads, I left feeling more inspired than ever by Basquiat's legacy and the urgency for greater representation in art.

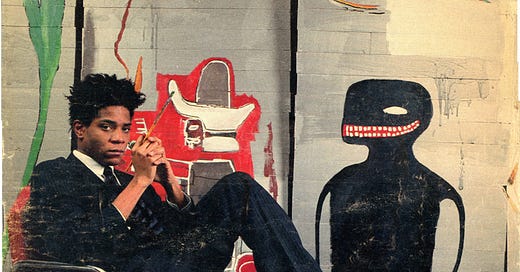

Basquiat tragically died at 27 of a heroin overdose. By then, he was already the most financially successful Black visual artist in history. Three years prior, in 1985, he had been on the cover of the New York Times Magazine, celebrating his meteoric rise in the art world. And yet, his work was often dismissed as primitive and derivative—a “poser” as written in a particularly scathing article about Basquiat in the New Yorker in the early nineties.

Basquiat found himself trapped in a challenging position: navigating a predominantly white art world while being tokenized for his Black heritage. He was perceived as someone culturally relevant and "cool," yet never quite on par with the pedigree of his white counterparts. bell hooks in her review of Basquiat’s wildly criticized 1993 retrospective at the Whitney shared, “Looking at the work from a Eurocentric perspective, one sees and values only those aspects that mimic familiar white Western artistic traditions. Looking at the work from a more inclusive standpoint, we are all better able to see the dynamism springing from the convergence, contact and conflict of varied traditions. Many artistic black folks I know, including myself, celebrate this inclusive dimension of Basquiat…”. In essence, art critics didn’t have the context to appreciate his work nor the desire to step outside of the world they knew to try to understand it.

Even with his most recognizable motif, the crown, its symbolism was often misinterpreted. As hooks observed in the same article, it wasn't just an emblem of status but also a reflection of Basquiat's aspirations within a restrictive industry: “Fame, symbolized by the crown, is offered as the only possible path to subjectivity for the black male artist,” wrote hooks, “Basquiat wanted a place in history, and he played the game.” Basquiat's successes are undeniable: his piece, "Untitled (1982)", fetched $110.5 million at an auction in 2017, the highest price ever paid for the work of a Black artist.

Despite the impact of Basquiat, the modern art world remains stubbornly unchanged, still ensnared by a traditional Eurocentric perspective. A 2019 study starkly highlighted this imbalance: 85.4% of artists represented are white, with 75.7% being white men. These statistics are not just cold numbers but reflect a deeper cultural resistance. As Greg Tate argued in his 1999 piece about the impact of Basquiat, Jean-Michel Basquiat Flyboy in the Buttermilk, “No area of modern intellectual life has been more resistant to recognizing and authorizing people of color than the world of the “serious” visual arts. To this day it remains a bastion of white supremacy, a sconce of the wealthy whose high-walled barricades are matched only by Wall Street and the White House and whose exclusionary practices are enforced 24-7-365”.

Basquiat's journey underscores the imperative to amplify diverse voices in art. bell hooks began her review of Basquiat with this sentiment, “If art moves us—touches our spirit—it is not easily forgotten. Images will reappear in our heads against our will. I often think that many of the works that are canonically labeled “great” are simply those that lingered longest in individual memory. And that they lingered because while looking at them someone was moved, touched, taken to another place, momentarily born again.” So let’s champion the art that makes us feel something—not just representation for representation’s sake, but to shed light on diverse narratives and artistic expressions, ensuring that they find their rightful place in the world.